Removing the roadblocks to corporate innovation -- when theory meets practice

By Steve Blank

Innovation theory and innovation in practice are radically different. Here are some simple tools to get your company’s innovation pipeline through the obstacles it will encounter.

—

Pete Newell and I’ve been working with Karl, the Chief Innovation Officer of a large diversified multi-billion-dollar company I’ll call Spacely Industries. Over the last 15 months his staff got innovation teams operating with speed and urgency. The innovation pipeline had been rationalized. His groups whole-heartedly adopted and adapted Lean. His innovators and stakeholders curated and prioritized their problems/idea/technology before handing them off.

Karl’s innovation pipeline had hundreds of employees going through weekend hackathons. 14 different innovation teams were going through a 3-month I-Corps/Lean LaunchPad program to validate product/market fit. His organization had a corporate incubator for disruptive (horizon 3) experiments and provided innovation support for his company’s operating divisions for process and business model innovations (Horizon 1 and 2.) Karl’s innovation process looked like this:

(Read our last post for the details.)

Given all this activity we were surprised that in our last call with Karl he started with “I think they’ve beaten me down.” He listed the internal obstacles his teams continued to face, “We’ve created innovation teams in both the business units and in corporate. Our CEO is behind the program. The division general managers have verbally given us their support. But we’re 15 months into the program and the teams still run into continual roadblocks and immovable obstacles in every part of the company. Finance, HR, Legal, Security, Policy, Branding, you name it, everyone in a division or corporate staff has an excuse for why we can’t do something, and everyone has the power to say no and no urgency to make a change.”

The reality is that Karl’s innovation pipeline looked like this:

And worse, every time Karl negotiated to remove a roadblock for one team, he was back negotiating 6 months later to remove the very same one for a different team.

Karl was frustrated, “How do we get all these organizations to help us move forward with innovation? My CEO has been reading all the Lean Innovation books and wants to fix this and is ready to bring in a big consulting firm to redo all our business processes.”

Uh oh.

Recognizing the Roadblocks

Most of the impediments the innovation teams faced were pretty tactical: for example, an HR policy that said the innovative groups could only recruit employees by seniority. Or a branding group that refused to allow any form of the Spacely name to appear on any minimal viable product or web site. Or legal, who said minimal viable products opened the company to lawsuits. Or sales, who shut out innovation groups from doing customer discovery with any existing, or even potential customer. Or finance, who insisted on measuring the success of new ventures on their first year’s revenue and gross margin. Or purchasing who insisting that the teams use their existing vendors that took weeks to deliver simple purchases that Amazon would deliver overnight.Listening to this we realized that while the company had playbooks for execution, what was missing were specific processes for innovation. We agreed that the goal was not to change any of the existing execution processes, procedures, incentives, metrics but rather to work with all the organizations to write new ones for innovation projects.

And the specific innovation policies would grow one at a time as needed collaboratively from the bottom of the organization, not top down by some executive mandate or consulting firm.

Read this section again. The creation of the innovation policies incrementally by the innovation groups collaborating with the service organizations is a very big idea.

We pointed out to Karl, that if he was successful, innovation and execution policies, processes, procedures, incentives, metrics would then co-exist side-by-side. In their day-to-day activities, the support organizations would simply ask, “Are we supporting an execution process (hopefully 90% of the time) or are we supporting an innovation process?” and apply the appropriate policy.

We offered that a top-down revamp of every business process should be a last resort. We suggested that Karl consider trying a 6-month experimental “Get to Yes” program. (It was critical that his CEO is a supporter.)

Get to Yes

Step one was that Karl needed a single memo from his CEO to his direct reports. We suggested that Karl ask for something like this:

Step two was that Karl needed a memo that went out to all department heads. The one from Finance looked like this:

The “Get to Yes” Collaboration

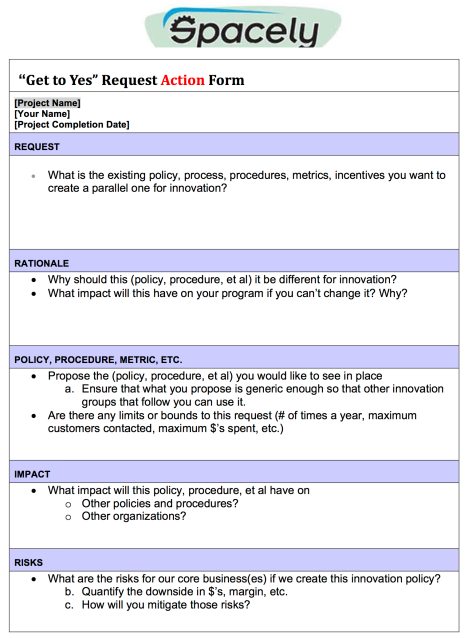

Every time an innovation team needed a new policy, procedure, etc. from an existing organization (legal, finance, sales, HR, branding, etc.), they worked with their designated point of contact (Finance, HR, Legal, etc.) Working together the two groups used the single-page standard Spacely “Get to Yes” form. It asked what problem the team was trying to solve that required a policy change, how it wanted the new policy to read, the impact the new policy would have on other policies and organizations, and most importantly the risks to the core existing business.The “Get to Yes” request form looked like this:

In practice, once the finance, legal, and other organizations had gotten top-down guidance that innovation needed solutions to move forward, in 70% of the instances the approvals could be worked out at the lowest part of both organizations.

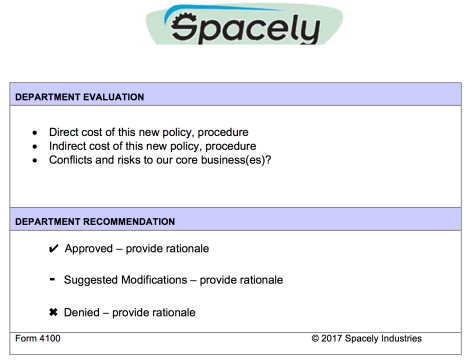

For the times that the innovation team and point of contact couldn’t agree, the issue got escalated to the appeals board of the appropriate department (legal, hr, security, finance, etc.) They had one week to ask questions, gather information, meet with the innovation team and evaluate the costs and risks of the proposed process. They could either:

The escalation form looked like this:

Although it was just a one-page form, the entire concept was radical:

For the few issues that the innovation program thought needed the executive staff attention, one further appeal was possible to the Chief Innovation Officer.

The big idea is that Spacely was going to create innovation by design, not by exception, and they were going to do it by co-opting the existing execution machinery.

The key to making this work was: 1) a simple top-down request from the CEO to their direct reports and from their direct reports down their organization, 2) a collaborative solution seeking partnership between innovation and execution teams, 3) an appeals and escalation process that would be acted on within the next week. And it’s there that the execution department had to make its case of why this request should not be approved. (If there was still no agreement, it became an issue for the executive staff.)

The time for a process resolution in a billion-dollar corporation – two weeks. At Spacely innovation was starting to move at the speed of a startup.

(BTW, when we showed this process to a government agency their first response was, “Oh that will work in a company, but in a government agency we’re bound by laws and regulations that mandate specifically what we are allowed to do.” So, we modified the Get to Yes program to ensure that a “No” had to specifically point to the law or regulation, not agency legend, then confirm there was no potential exception to the regulation or law that could be applied.)

Lessons Learned

Read more Steve Blank posts at www.steveblank.com.